When he was nine years old, Howard Ingber got a chemistry set for Christmas. By the time of the first explosion, Ingber was hooked.

“Explosions, smoke, gunpowder, sulfur. The kit showed you how to make nitrocellulose (guncotton),” Ingber remembers. “Today you’d have 16 lawyers on your back if you tried to show a kid that.”

Three years later Ingber got a job as a pharmacy delivery boy, where he watched drugs being compounded. Those two experiences convinced Ingber to be a chemist. That is, until he met an actual chemist who told him he’d be more employable with a degree in chemical engineering. So chemical engineering it was.

Ingber’s first ChemE class — stoichiometry with Professor Thomas Hanratty — didn’t occur until his his junior year. Up until then his courses had been identical to those majoring in chemistry.

“Dr. Hanratty was a great teacher,” remembers Ingber. “He instilled in me a love of chemical engineering. I remember he always told us it is not an exact science like algebra.”

As wonderful as his academic experiences were at Illinois, Ingber does not recall any socializing between undergraduate students and professors, despite there being only 17 students graduating in each semester of 1956.

Still, Ingber always felt indebted to the program. He’d studied under “brilliant people … I couldn’t do what I did without them.” That included, not only professors like Hanratty and Harry Drickamer, but also Ingber’s classmate, John Zahner (BS’ 56, MS ’59, PhD ’65 all under Drickamer), “one of the smartest guys I ever knew … he could read a book one time and absorb it all … he could look at a problem and figure out in his head the best path to take to solve it.”

As dedicated to the department as he was, Ingber gradually lost touch with the people there. That is, until department chair, Professor Paul Kenis came along.

“When Dr. Kenis called it was like a magic thing,” says Ingber. “ He was going to be in the Los Angeles area and he wondered if he could come by. I felt so good to be contacted by someone from the department after 63 years. He is a real people person. I only wish I had someone like him in my time.”

Ingber loved chemical engineering. He loved the process equipment (distillation towers, reactors, heat exchangers, etc.) and the electronic instrumentation used to control them. He predicted that the slide rules, which the engineering students carried like sabers attached to their belts, would eventually be replaced by digital calculators based on his experience with one of the first such devices, the ILLIAC.

Imagining that one day the engineers with their slide rules would be replaced with a digital computer Ingber specialized instead in the field of control instrumentation.

After graduation, Ingber headed to work with Standard Oil of Indiana. He was in at the “very, very beginning of the implementation of continuous process analyzers.” When a large plant is processing crude oil, for example, operators need to make sure that variables like chemical composition, boiling point and viscosity are within the proper specifications. Before continuous analyzers, it might take three days after the operator took a sample to receive an analysis from the plant lab. So if the sample wasn’t up to specification that could result in thousands of barrels of product that needed to be blended or processed again. Continuous process analyzer data , which the operator had confidence in, were absolutely critical to the bottom line, he said.

About three years after he graduated, Ingber discovered California.

“I had a Jaguar XK 140 convertible and I visited a relative in Los Angeles,” says Ingber. “I was driving with the top down on New Year’s Eve and I said to myself, ‘this is where my car belongs!’”

So Ingber moved to Los Angeles. He had realized that selling instruments might be perfect fit for him and so it was. Soon he was a successful salesman of continuous process analyzers.

But again and again, he’d observe that a new plant might have 130 analyzers and only three would work correctly at start-up. By the time the analyzers were operational it was too late, operators ran the plant without them.

The problem, he realized, was that although the engineering drawings were correct field pipefitters, who were very good at installing 6-24 inch pipe, often did not appreciate some of the nuances of bending and installing 1/8 -1/4 inch stainless steel tubing. Likewise, they didn’t understand any of the product physical chemistry involved; if a sample separated into two phases, it would become impossible to analyze.

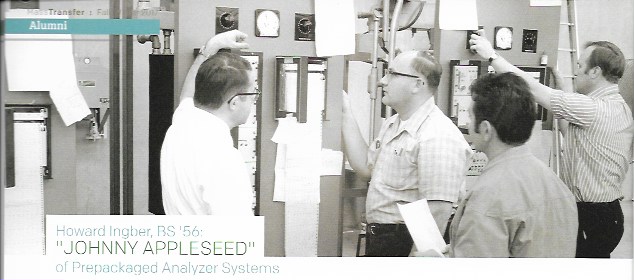

So Ingber pioneered the idea of pre-packaging all the small-diameter piping, various electrical conduits, and terminal boxes associated with the analyzers in a common “house.” This self-contained unit enabled control of key factors like temperature, tubing installation and more. By assembling the houses in a controlled environment, Ingber’s team could work out the kinks and train the plant maintenance people under conditions less stressful than at plant start- up. Refinery projects went from having three analyzers working at start up to having almost all analyzers working at start up. This saved companies hundreds of millions of dollars in off-spec product and Ingber’s company was in high demand.

In order to design, manufacture and install these integrated systems, he bought a control panel manufacturing company, and began to sell integrated analyzer systems. Within six years the company grew from two employees to 180.

In the early 1970s, having sold his company to Envirotec, Ingber moved his family to Paris and worked for Comsip Entreprise, a French company, to start a new division and spread the gospel in Europe and South Africa.

“I felt a kind of missionary zeal to convince people that this is the way to install analyzers,” he says. “I was like the Johnny Appleseed of prepackaging.”

He was even invited to China in 1979 to speak about continuous process analyzers. The Chinese had tried to reverse engineer the analyzers but they didn’t understand the principles, Ingber says. He spoke in Shanghai, Peking, and Nanking and visited many refineries and chemical plants and did not find one working analyzer. “At one refinery they had a guest book for visitors to leave a comment about their visit, but it was almost empty. The only other comment was that of Arnold O. Beckman.”

Ingber is both proud of his achievements but also dismissive. “It’s just a technique,” he says. “It doesn’t have my name on it.” But in the same breath he’ll say, “It’s especially satisfying that that’s how people install process analyzers all around the world. Now it’s the industry standard.”

0 Comments