NCTE Council Chronicle March 2013

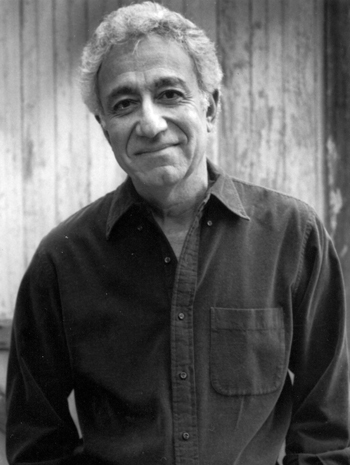

Mike Rose has a message for teachers working with struggling students: keep the faith, because your effort really does pay off far down the road.

“You’ll be surprised how many of these students remember, ‘my teacher in 9th grade said I should consider going to college,’ or whatever,” says Rose. “That time spent when the students are having a hard time, you may not see the pay off, but it registers.””

Throughout his career Mike Rose has been a powerful advocate for students who, for a variety of reasons, have fallen through the cracks of the educational system.

In his latest book, Back to School: Why Everyone Deserves A Second Chance at Education, Rose spotlights the role of “second-chance institutions,” such as community colleges and adult education programs. He believes they can provide essential resources for these “non-traditional” students as they redirect or augment their lives.

As older students, low-income students, and those enrolling in two-year, rather than four-year institutions, become the norm, the need for second-chance institutions is growing. However, even as demand grows, these institutions are under attack by politicians looking for ways to balance their budgets, says Rose.

“During this time of people doubting the value of higher education, during this time where there is doubt as to whether or not we can afford to create the conditions for people to get a second chance, this book, I hope stands as a kind of testament to the ideal of a second chance society, to the ideal of creating opportunity for those who have not had an easy time of it,” he says.

Back to School

Rose is motivated by his strongly held belief that everyone, even if they did not grow up with a computer in their room — or even a room of their own — has a desire to acquire knowledge, gain competence, and perhaps redirect their lives. Rose has witnessed this over and over, both in the course of researching his books and in the classroom, where Rose has taught returning Vietnam veterans, inner city children and community college students.

Rose understands very well what non-traditional students experience. Growing up poor in Los Angeles with parents who had virtually no schooling, Rose was mistakenly put in a vocational track. College was not on his radar until a high school teacher lit a fuse under him. Even then, without the help of several college professors he would not have succeeded.

Today Rose is professor at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. Several of his books, particularly Lives on the Boundary: The Struggles and Achievements of America’s Underprepared, are considered canonical texts. Back to School is his latest effort to put a face on those who are on the outside looking in; the very people who need second-chance institutions.

“Most people out there have somebody in their family, or a neighbor, or friend, who wants to, needs to go back to school,” says Rose. “School is not a cure-all but it is one avenue where things happen.”

To research Back to School Rose spent two years at several community colleges, observing and interviewing students. He introduces readers to a former gang member, Henry, who was paralyzed by a gunshot and eventually returned to school, where he changed his life. Henry first enrolled to earn a certificate as a computer security specialist. But after spending time on the campus he realized he didn’t just want his certificate, he wanted to take general education courses. Now Henry has completed his associate of arts degree and is applying to four-year colleges. Another student, an ex-marine who had been in and out of prison, is now a double major at a state university in linguistics and conflict resolution.

“I want to learn math this time,” a third student told him. And, gesturing toward the campus she added, “You know I really like this. I didn’t know it was going to be this good.”

There are many different roads to college and to intellectual pursuits, Rose believes. Second-chance institutions help pave some of those roads.

“The more varied those pathways, the more personal histories, the more points of view, the richer we are for it,” he says.

Responding Fully

So many students Rose talked to were energized and inspired at the prospect of continuing their education, no matter the obstacles in their paths. And the return on investment in these students can be enormous.

“You can’t spend two years watching the desire that starts to emerge and seeing what’s possible, and not see [these students] as a huge untapped resource,” says Rose.

To respond fully and well to those students who come to these second-chance institutions, Rose believes, we must move beyond the ready-made labels and explanations and understand what exactly it is each individual student needs from everyone within a college community, from teachers to receptionists. Back to School is Rose’s effort to explore how we can come “to see students not necessarily as what they are not, but as what they could be.”

One key is to rethink remedial education, particularly writing instruction. Many educators are recognizing that using drills and workbooks does not give students tools they need to succeed in college. The drills and workbook approach is based on the belief that to learn a complex task one must break it into simpler ones, but research has shown that reading and writing instruction does not follow that model.

Remedial writing instruction instead should seek to reframe the way students think of writing, says Rose. The main messages for students? That writing is a way to clarify and give order to ideas; that there is more to good writing than being grammatically correct; writers communicate with an audience; and editing and multiple drafts make for stronger writing.

In the process of learning these things students work on and discuss grammar and punctuation, but it takes place within the context of these other tasks, so that the need for grammar and punctuation makes sense.

Numbers Hide Nuances

One argument for reducing budgets or raising entrance requirements to community colleges is to reduce the, admittedly high, drop-out rate. While he acknowledges that second-chance institutions can be improved, looking merely at numbers like graduation rates without anecdotes like the ones Rose provides means we miss potentially important nuances hidden in the numbers.

For instance, Rose knew of one young high-school dropout who entered an electrical construction program and got absorbed in school, developed some literacy, math and trade skills and began to see himself in a different light. He quit before completing his certificate in order to join the Navy, where he could continue his education, clear his debts and have a potential career before him. In a statistical sense that student is a drop out, but most would consider him a success story.

“A purely statistical analysis reduces students’ lives and aspirations,” Rose says.

Those aspirations can include wanting to do something good for yourself and your family; feeling your minds working and learning new things; being better able to help your kids with school; remedying a poor education, having another go at education and changing what it means to you; learning new things and gaining a sense and certification of competence; or even redefining who you are.

Rose has spent much of his energy bridging the divide between poor, working class students and instructors among the academic elite. People who are striving against tough odds deserve our focused attention, Rose believes.

Sometimes that means reminding teachers that some students won’t automatically know what office hours are or how to make use of them. Sometimes it’s showing students’ lives to teachers so that they understand that the man falling asleep in the front row isn’t apathetic, but coming off a night shift. Or the student who doesn’t turn in writing assignments might be wrestling with self-doubt so strong it makes her sick to her stomach.

Rose has specific recommendations for K-12 teachers working with underprepared students. First, to bear in mind the kinds of tasks students will need to master to succeed in college and focus learning on those areas.

Rose also recommends providing concrete examples and illustrations. Don’t just talk about what makes good note taking and what doesn’t; pass around examples of the good and the not-so-good.

Rose doesn’t advocate taking pity on nontraditional students, or somehow “dumbing down” the curriculum for them, but he does encourage teachers to work to fully understand their students’ situations. The more a teacher understands, the more the environment in the class can become a safe place, a community of shared intellectual exploration. Which is, after all, the key to learning, no matter the level or circumstances of the learner.

0 Comments