If Marilyn Scudder Barnwell was a super hero she would be the Compassionator. As for her fatal flaw (because every hero has one), perhaps it would be a humility so deep that it renders her short-sighted about her own accomplishments. The evidence? When Dinah Volk, chair of NCTE’s Early Childhood Education Assembly (ECEA) tried to nominate her for ECEA’s 2015 Early Literacy Educator of the Year Award, she refused it.

Barnwell, the education director for the Bloomingdale Head Start Family Program, a bilingual, multicultural, inclusive, family-centered program in New York City, is the first administrator to receive this award. The past recipients have been research faculty or classroom teachers.

“At first I declined because I didn’t do research or teaching or anything,” she says. “But then there was a mutiny at the school. They forced me to reflect on what I do [and to see] I don’t value it the way others do.”

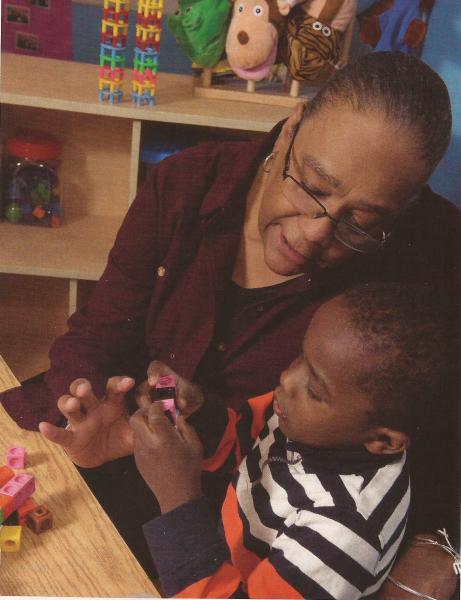

As the education director, Barnwell oversees and supports the school’s approximately two dozen teachers. She encourages her teachers to be lifelong learners, supporting them as they earn degrees and helping them set aside time to study.The respect, trust and compassion with which she treats every teacher creates a nurturing and supportive environment that, in turn, empowers children and their families.

Honoring Barnwell “is a great way to open up the conversation and say, ‘look at how an administrator is one of the most profound literacy educators in the lives of young children,’” says Dana Bentley, a teacher and member of the nominating committee.

“I love the idea that literacy is something that happens in all facets of education. When we confine it to just the teacher/educator, or just the classroom teacher, we really narrow the meaning of literacy in education as a whole.”

The Bloomingdale Family Program is located in a diverse neighborhood on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Each of the 11 classrooms is bilingual. In addition, more than half of the teachers are former or current parents and come from the neighborhood. Although this has been the case for the 55 years the Bloomingdale Head Start program has existed, Barnwell nourishes it.

‘We’re really fortunate to allow people to grow in their own soil,” says Barnwell.

Because of her own worldview, Barnwell sees the potential in every parent, teacher and student. She approaches each person as an individual with worth and something to contribute.

Barnwell supports literacy by honoring the various backgrounds and cultures each family brings to the school, says Bentley. “She sends the message to families that ‘you are coming here with a wealth of knowledge. We will learn from you and we will learn with you.’”

Even though Barnwell does not speak much Spanish, she makes everyone feel welcome.

“Marilyn can look at your eyes. She can read inside you because she really cares,” Bloomingdale Family Program teacher Yandra Mordan-Delgadillo told the award committee.

“All the classrooms are bilingual. Some teachers get very worried about that,” says Joyce Dye, another Bloomingdale teacher. “They say, ‘I don’t understand what the child is saying.’ Marilyn tells them to watch the children play together. ‘Do you have to know a language to interact with a child? Don’t let that be your reason for not getting to know that child,’ she says. She has a way of helping without making you feel little. We teachers need trust too. She always brings it back to the children.”

Barnwell didn’t realize what she was doing was “a thing,” she just did what made sense to her. Take teacher assessment, for example. She remembered how she would feel as a classroom teacher when someone observed her class. Not scared, exactly, but uncomfortable. So she began using videotape at Bloomingdale instead. The first thing she did was give the tape to the teacher, for them to watch on their own before Barnwell met with them. Often the teacher could see for themselves what they needed to improve and sometimes they’d say to Barnwell, after viewing the tape, “can you come back and tape me again?”

Barnwell’s supportive and collegial manner comes so naturally she has never really thought about her approach.

“I couldn’t write a proposal about it, or describe for anyone, as in ‘these are the steps to take,’” she says. “It’s just my style and has been throughout my career.”

That style grew from being a lifelong learner, and having empathy for others who may have been underappreciated or prejudged, as she was as a child.

Barnwell grew up in the 1950s and, despite being in gifted classes, was told that, because she is African American, she was not destined for college. After graduating, she took a job as a typist in the family services unit of the welfare department. She imagined this would be her entire career. However, when parents came in to talk to a social worker and they had children in tow Barnwell was put in charge of the little ones. Although at first she was intimidated, not knowing anything about children, the more time she spent with them, the more she enjoyed those interactions.

Soon Barnwell wanted to learn more about the development of young children. She found a community college that taught early childhood studies.

“I realized ‘I’m not stupid, I can learn,’” she said of that very successful academic experience.

From there she earned both her bachelor’s (Fordham) and her master’s degree (Columbia Teachers’ College), while teaching and raising her own children. She never forgot that feeling of being told she wasn’t smart enough and then discovering that she, in fact, was. It helped her understand that people often have untapped potential.

Another formative experienced occurred when she worked with a teacher who continually praised herself, although based on Barnwell’s observations, the teacher had let her skills slip.

These two experiences made Barnwell vow to never feel superior to anyone, and always keep learning.

Barnwell had been working as a classroom teacher when the position as director of education of Bloomingdale Family Program became open. Although she wanted the job, she dreaded being in charge of other people. Who was she to tell others what to do?, she worried. Still, the first week she went from classroom to classroom and made a list of things teachers should change.

Then she had an epiphany. She realized that that was her list, the things she’d change if she were in charge of each classroom. But she needed to have trust and faith in the teachers.

She tore up the list and went back to each classroom to observe and learn from each teacher. And that’s what she’s been doing for the last 35 years.

“From that day forward,” she says, her method is to “go into a classroom and learn other ways things can happen.”

She might see a teacher being very patient with a child having a difficult time and observe the way that teacher is being patient. Or how another teacher creates an environment in which two or three children speaking different languages can play together.

Barnwell reframed her position as an opportunity to learn from other teachers. “Every teacher has strengths,” she says. “My job is to identify and nurture those strengths and encourage teachers to share them with one another. It may not be conventional, but I see who they are, which allowed them to be who they wanted to be.”

She is such a strong supporter of what she calls “my families” and “my teachers” that she advocates for them well beyond the Bloomingdale building.

For example, when Barnwell recognized that the transition from the Head Start program to the city schools was difficult for families, she stepped in. She is active in a group called the PLP, Parent Leadership Project (an outgrowth from an earlier parent group), that help parents facing that transition. The group discusses, not only the process of how to choose a school for their children and what their rights are within the school system, but also how to confront the racism they often face. Parents who do not have strong English skills often bump into hostility at schools they are visiting. The PLP developed a model where an English-speaking parent and a parent without strong English visit a school together.

“We learned you cannot go alone … parents support one another in this way,” says Barnwell.

For someone who works so hard to validate and support others, Barnwell struggles to accept praise and recognition. The NCTE award has made her think maybe it would be “healthier” if she started believing the praise others give her. Her next lesson? To “practice owning this as mine,” she says. Because, when all is said and done, Barnwell cherishes the NCTE award. It tells her “you’re a part of this field too.”

“I do not like attention, but this award has helped me really reflect and see my work in a different way,” admits Barnwell.

0 Comments