Bringing His Unique Perspective to the SWR

NCTE Council Chronicle March 2013

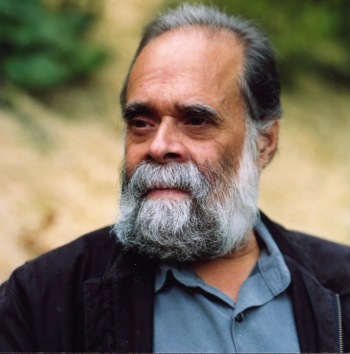

Victor Villanueva is energetic and enthusiastic when talking about his new role as editor of the Studies in Writing and Rhetoric (SWR) monograph series.

“It is a very exciting time for our field,” he says. “It’s the time to be doing this thing.”

Perhaps it is also a way for him to remind himself and others that, in addition to his long list of achievements and credentials, in addition being intimately woven into the fabric of academic life, he is also “other,” a Brooklyn born, Puerto Rican high school dropout who earned a PhD by way of the military and community college and has had a successful 30-year career as a teacher of rhetoric and writing.

In either case, there is little doubt that Villanueva, who has begun his five-year tenure as editor, will spice up the venerable SWR.

The SWR was created in 1983 by NCTE’s constituent group, College Conference on Composition and Communication (CCCC), and is considered, according to Villanueva, the “premier monograph series for our fields.”

“I look at rhetoric more than composition studies and my scholarship has to do with rhetoric and racism, so once it was announced that Joe [Harris, who studies writing more than rhetoric] was stepping down we got flooded with manuscripts” on related topics, says Villanueva. “The last six months have been incredible.”

Rhetoric and Racism

So what does he envision for the SWR under his leadership? Personally, he is interested in proposals that address the rhetoric of racism “writ large.”

Villanueva says that people think of racism and race with regard to minorities, what he calls special-interest groups.

But, he says, ”the rhetorics of racism is not the rhetoric of interest groups it is the rhetoric of interest, of hegemony,”

“It’s those in power who separate out the special interest groups. Part of what I teach is, why is it important to the political economy to make women, blacks, Indians, etc, inferior? In terms of rhetoric, what is happening?

“We think racism is normal, natural but it’s not, it’s new. It’s only 500 years old,” he says. “Now the old white guys’ arguments no longer appeal to the majority. Why is that? I’d like to see a hell of a lot more of this in the series.”

He has received a couple proposals on the rhetoric of African Americans but hasn’t seen any about the rhetoric of Latinos, or of Asians, for example.

“Asian Americans have been bigoted against for being so successful,” he says. “Rather than being accepted we see them as a ‘model minority.’ In other words, still ‘other.’”

Villanueva has been surprised at the number of proposals on the rhetoric of faith and religion that have landed on his desk.

“I’ve never written anything about faith and teaching of writing, but I have received four proposals on that topic,” he says. He also received two proposals within a month having to do with evangelicals. He found this intriguing, while acknowledging that “I know those are our students and we are not well equipped to deal with them.”

Digital Deluge

But by far the most pressing issue, according to Villanueva, not just at the SWR but within the field of rhetoric and writing generally is that of teaching rhetoric in a digital world. The future of rhetoric, he says, rests on the degree to which “we recognize we are moving away from ‘stains on leaves.’ We are all digital now. Writing is going way beyond the idea of linearity and of writing on paper.”

He points out that most students in his classes were born in 1991 and the Internet was “born” in 1995. This is a generation, more than any other, has grown up digital.

“When I think about SWR and I think about our field and I think about the job that we have ahead, it is a matter of understanding what it is we do within the digital paradigm,” he says. “The digital paradigm is moving us into new places and we’re going to have to think about text differently as we move forward. But as we move forward we also have to think about the baggage we bring with us. And that baggage includes certain notions about sexuality, about gender, and about racism that we are not quite being conscious of because we have old language to go with that.”

Today students write more than any generation in history, but their texts are not the same texts taught in the classroom. Scholars need to both recognize the degree to which the digital has taken the field to new realms and also figure out how to both acknowledge this new discourse and also work real “logos” into it, says Villanueva.

“One of my daughters said to me the other day, ‘I see the sense in what you’re saying but I don’t think what you’re saying makes sense,’” says Villanueva. “So how do we incorporate what we think of as viable arguments into the kinds of argumentation they already employ?”

“These kids know technology in ways we can’t know, but that doesn’t mean they know everything,” he adds. “We have 2,500 years of alphabet literacy, of knowing how language operates, versus the last 10 years, which, admittedly have been like going from the oxcart to international travel in a decade” in terms of the speed of change.

“How can what it is they know be influenced by what it is we know?” he asks. “There is a way in which we need to come together. It’s a mutual education process. That’s the future of our business; that’s the future of this monograph.

“I’d like to leave a mark as editor who brought us to this new age,” he adds.

Right now Villanueva is seriously considering several manuscripts, including one on “freedom writing,” which examines African-American literacy traditions; one on new media with a co-author looking at new media from a lesbian perspective; one on how universities can engage with communities in writing partnerships; and a theoretical manuscript on “responsible writing” that embraces uncertainty and remains responsive to the voices and concerns of others.

Some early efforts have been made to think about this new paradigm, but in Villanueva’s mind they are not fully developed and “an argument that hasn’t been well formulated is too easy to dismiss.”

He compares these early efforts to tostones, plantains (platanos) that are still green and boiled in oil. They are good, he admits, but the really great platanos are platanos maduros, which are yellow, even black, and ripe, sweet, soft and delicious.

Villanueva is looking forward to putting his stamp on the SWR, and given his passion and commitment, that seems inevitable.

0 Comments